It’s quite apt that this first post here on What Data Shows focuses on what data doesn’t show.

Notwithstanding the irony, I think it makes an especially pertinent starting point in today’s “post-fact” world where passing off half-truths, opinions, exaggerations and even fantasies as facts is the frightening new normal.

A little bit of data and a lot of opinions results in some great fiction.

Which is what bothered me as I read this Guardian article a couple of days ago: ‘Risk-averse’ NHS 111 sends more callers to A&E than previous service’.

Now Guardian being one of my most read publications and one I’m a paying subscriber of, I really don’t like to hate on them here. But.

Four paragraphs in, I was still searching for answers to questions that had sprung to my mind after reading the alarming headline. What is the real reason 111 is sending more callers to A&E? What has changed? Who are the people calling in to the service? Are people sicker now as compared to previously?

Nope, no answers found. But Guardian did seem convinced that the 111 service is staffed by a bunch of incompetent people pushing people into A&Es because … wait, what do they even gain from it?

By the end of the article anyone who is worried about NHS’s current state would be outraged, probably agreeing that instead of being sent to A&Es, people should simply glue their arms back themselves and fix chest pains with a warm bath instead of popping in to their local A&E for afternoon tea.

The article’s claims and the data it refers to clearly contradict each other. So either the Nuffield Trust report was being misreported, or the actual report itself was jumping to conclusions.

Well. It turned out to be both when I looked up the Nuffield Trust report.

The report includes many conjectures with no evidence to back them. And media reports pounced upon these conjectures because these make easy attention-grabbing headlines in the midst of highly politicized debates over the NHS, facts be damned.

These are the data points that the Nuffield Trust report uses:

- The number of calls received by 111 as published by NHS England in its monthly performance summary for the helpline.

- Breakdown of call volume by the service callers are referred to (Ambulance, A&E, Primary care, Other service).

- Regional breakdown for the above.

- Results of NHS 111 surveys administered to some callers questioning what they might have done in the absence of the 111 service.

Briefly, what the actual report says is this:

- The proportion of people sent to emergency services has risen from about 18%-19% initially to 20%-22% recently. (Hardly a huge change over the 3 years it tracks, I say.)

- There is wide geographical variation in ambulance referral – from 8% in South Essex to 17% in North East England.

- Overall proportions indicate “consistently higher number of people sent to ambulance services compared to A&E. This is the opposite of what happens with patients in general, where far more people attend A&E than have an ambulance sent.”

- The report uses the above difference to suggest that there may be “some plausibility that NHS 111 is too risk-averse with people who have more urgent problems.” That’s it. A mere hypothesis. And nowhere else in the report is higher risk-aversion asserted.

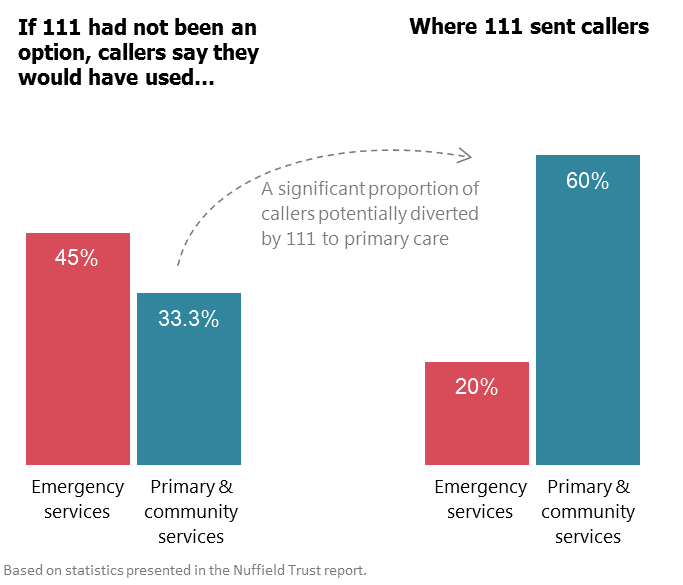

- NHS 111 diverts a significant proportion of people to primary care and other services who would have gone to emergency services in the absence of the helpline.

- There is no evidence that the helpline sends those people to A&E and ambulance who otherwise would not have gone. (Really, what are we all arguing about then?)

- During winter months when call volumes go by up to 50%, the proportion being referred to emergency services falls. (Again, what was the issue here?)

On the whole, the report defends the usefulness of 111 in preventing unnecessary A&E visits, while merely highlighting overall and regional trends in over- and under-referrals to A&E for further analysis.

And what to the major news outlets shout? That the incompetent “risk-averse” staff at 111 are sending people to A&Es unnecessarily and bleeding the NHS dry. Far from what the report itself, shaky as it is, states.

Where the real story is.

(tl;dr: Definitely not in this report)

To even begin to understand the recent uptick in A&E referrals and geographic differences, we need data which tracks the treatment these referred patients received at the A&E. Did these patients actually require emergency treatment or did they really just go in with period cramps and insect bites like Daily Mail claims? (Full marks to them for imagination.)

If more callers are being sent ambulances instead of being asked to go to A&E on their own, what is the reason for it? Are these people actually in need of ambulances, or do 111 staff like to give away complimentary rides to A&E as a free gift for calling? If they really are risk averse, what drives such behaviour? Are they overly nice, sympathetic people, or are staff incentives skewed in some way that they favour calling an ambulance?

What about all those people who go to A&E without calling first because there would be no point (like when someone breaks their leg or has a seizure)? Those need to be factored into the analysis too surely?

Is geographic variability entirely all down to differing degrees of staff risk aversion? Or are people in South Essex much healthier than the national average? You know what would actually make a great story? Actual reasons people in certain areas might be needing more (or less) emergency care.

We need answers to these and a lot more to figure out just what is going on behind 111 referrals. And for that we need a lot more data. Simple referral volume stats provide absolutely no explanation as to what’s going on behind the scenes.

A paradox is apparently something you didn’t bother to read properly.

But in a pickle because the statistics in the report (see chart below) don’t actually support the article’s premise, the article ends with:

“Paradoxically, NHS 111 is also reducing the pressure on A&E and ambulance services and successfully redirecting callers to GP surgeries and other services outside hospitals.”

Never mind that these figures contradict everything in the news report earlier, labeling them as a paradox is a convenient cop-out.

With those numbers in context, 111 seems to be doing its job by relieving pressure on A&Es, no?

Using opinion surveys to predict actual A&E usage statistics.

If there is one thing we learned in 2016, opinion polls asking people what they are likely to do are not reliably predictive of actual behavior of the whole population. Especially something as unpredictable as emergencies.

Asking a small set of callers whether they are likely to use emergency services in future can’t sensibly be compared to actual usage by everybody. Emergencies are exactly that – we can’t predict when they will strike.

People in general, other than the hopeless pessimists, don’t usually like to think that their future self will be unlucky or unhealthy . I didn’t think I’d get pneumonia at age 30 and end up in the A&E with chest pains so severe I thought I was dying. (For the record, 111 told me to go to the GP, who couldn’t see me. So I took myself to A&E which said I was right to come in when I did.)

Fact versus fiction

Isolated excerpts from the report were factually correct. But selective and disjointed reporting created an entirely different story from what the Nuffield report presented.

Come on Guardian, we expect better from you.

It wasn’t just Guardian though that went for the sensationalist, deliberately alarm-inducing angle. Take a look at some of the other news outlets who went way further in inventing “facts”.

To be clear, I’m really not defending the 111 service over NHS Direct, which was a deeply unpopular decision and for many good reasons.

What I am pointing out though is that the data in this report does not show risk aversion or any other causal link as many in the press would have us believe.

But between click-generating headlines and facts, I suppose it’s the former that come out on top.